I.

Most of the materials about the poet were collected in 1995, leading to the creation of the documentary film Incitatus, aired a year later. In the film, an attempt was made to restore the true biography of Count Vasily Alekseevich Komarovsky. In the process of preparing for filming and writing the script there were found autographs of poems, unpublished at that time, in the manuscript departments of the Russian National Library and the Russian State Library; unique material concerning the genealogy of Count Komarovsky was collected in the manuscript department of the Pushkin House; valuable consultations were obtained in the A.A. Akhmatova museum in the Fountain House and in the All-Russian Alexander Pushkin Museum. A number of documents were found in the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art and the Central State Archive of Literature and Art in St. Petersburg. The addresses and dates of Komarovsky's residence in St. Petersburg and Tsarskoe Selo were established. Some documents were graciously provided by relatives of V. Komarovsky, N. Punin, and the Kardovsky family. Professor N.A. Bogomolov of Moscow University participated in the creation of the film as a scientific consultant.

The film was broadcasted on VGTRK in 1996, and then was shown on LTV (Latvian Television) in 1997. A copy of the film was donated to the A. A. Akhmatova Museum in the Fountain House and is now available on the Internet on the YouTube channel.

* * *

A pleasant surprise for all researchers of the period of Russian literature, which until recently was commonly called the Silver Age, was the publication in 2000 by the publishing house of Ivan Limbakh of an excellently published book of works by Vasily Alekseevich Komarovsky. “The publication of this book is in many respects a very, very remarkable phenomenon. First of all, it gives the modern reader the opportunity to perceive the author's texts not from blind reprints of who knows what time, but from a reliably verified text. Before that, there were two editions of V. Komarovsky's works – a lifetime edition of 450 copies, which has long been a rarity, and prepared by George Ivask & H.W. Tjalsma in 1973 for the Munich publishing house Wilhelm Fink Verlag, which practically did not get into Russia, and is quite rare in the West. Thus, the poems of the poet, who is rightly considered one of the most significant for the creation of the poetics of acmeism, turn from a rarity into a living literary fact”, – wrote Nikolai Bogomolov in a review of the publication of the book.

And, indeed, the compilers of the book Igor Bulatovsky, Irina Kravtsova and Andrey Ustinov have done a great job. The book includes almost all the surviving works of Komarovsky (62 poems, one story, several prose passages, 53 letters), memoirs about him (Nikolay Punin, Sergey Makovsky and others), materials for his biography, as well as an album of the poet's drawings and a large number of photographs. The book includes three studies belonging to the largest connoisseurs of Russian poetry – Vladimir Toporov, Tomas Venclova and Tatjana Tsivjan.

In 2002, through the efforts of the same researchers, a reprint of the first and only poetic collection of the poet The First Pier was published, supplemented with newly found poems and commentaries.

In 1995-1996, the author personally met with the compilers of these editions, and then, after the film aired, consulted them several times by telephone regarding the location of some of Komarovsky's autographs.

II.

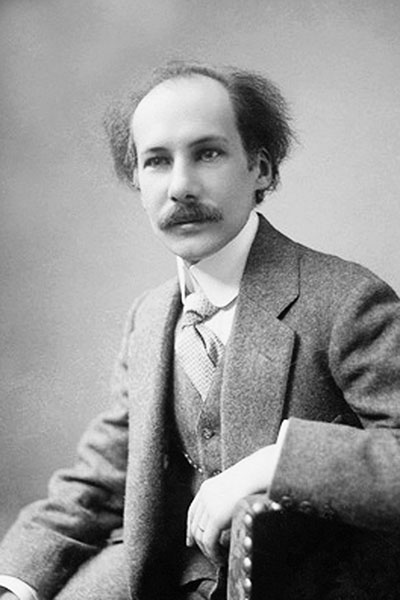

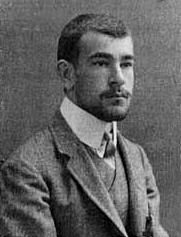

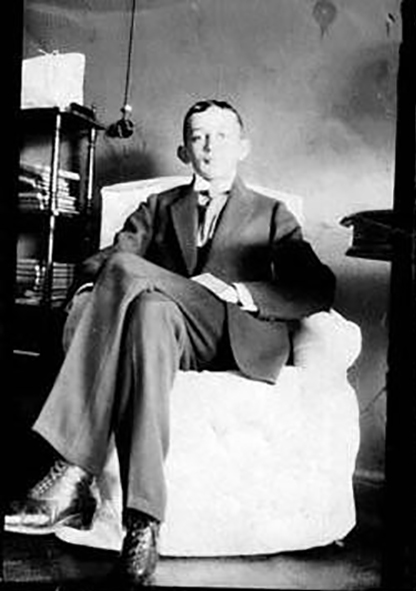

Vasily Komarovsky. 1899-1900

Around any large (and sometimes not very large) literary name, there is usually a certain halo, which is not always clearly traced by our consciousness, but often affects the reader's perception even more than the actual literary work of this or that author. This halo sometimes turns out to be much more significant than the literary heritage, to a large extent changes, and sometimes even distorts its true content. This kind of literary image is formed gradually, born from creativity and personal fate, enriched by a literary reputation, supplemented by near-literary legends and, ultimately, acquiring the depth and significance of a myth. In the future, such a myth, receiving more and more generalized, almost symbolic meaning, replaces the figure of a specific creator. One of the prerequisites for the formation of a myth is often the literary reputation that develops around the name of an author.

In the now classic work by I.N. Rozanov Literary reputations there is no clear definition of this concept itself, so we will use the interpretation of N.A. Bogomolov, who singles it out from the text: “The content of the term includes only the reaction of external interpreters of the work and the author’s total creativity: reviews, critical reflections, parodies, rehashings, citations, inclusion in anthologies, etc., up to the installation of monuments and simply saving in memory of grateful (or, conversely, exceptionally ungrateful) descendants”.

“However,” continues N. Bogomolov, “in the concept of literary reputation, there inevitably exists a second side, relating to the writer himself: creating not in an airless space, he inevitably reacts to critical responses and everything similar to the above, correlating the true content of his work, to which it presents itself to him with that external reception which is expressed in the responses of the “literary community””.

Thus, literary reputation is formed, so to speak, as a result of the interaction of external and internal factors. If the external factors include the reaction of contemporaries (and especially descendants), then the internal factors will be the direct work of the author and his ideas about how his contemporaries, the “literary community” see his work. But among the internal factors, it is necessary to note those actions that the author consciously or unconsciously performs in order to correct the perception of his work by contemporaries. These actions can be both purely literary in nature (actual literary work, critical articles, prefaces, participation in literary discussions, etc.) or act as internal causes of everyday everyday behavior. This behavioral activity takes its wearer beyond the scope of “literary reputation” as such, creating the desired halo around his personality rather than around his work. The author's desire to merge literary creativity and behavioral activity into a consistent unity is especially characteristic of the era at the turn of the 19th–20th centuries.

The turn of the century has long been firmly associated in our minds with the concept of the Silver Age. For the ancients, the golden age was an eternal spring and did not know the seasons. The seasons came with the silver age. The Silver Age of Russian culture opened the flourishing complexity of history. “The old ideal of classically beautiful art has completely faded, and it is felt that there is no return to its images. Art convulsively seeks to transcend its limits. The boundaries separating one art from another and art in general from what is no longer art, what is above or below it, are being violated. Never before has the problem of the relationship between art and life, creativity and being, been so acute, never before has there been such a thirst to move from the creativity of works of art to the creativity of life itself...” – Nikolai Berdyaev wrote about this time.

The desire of art to go beyond its limits led, in particular, to the variant of life-creation, which Vladislav Khodasevich recalls in Necropolis. “The Symbolists,” he writes, “did not want to separate a writer from a person, a literary biography from a personal one ... It was a series of attempts, sometimes truly heroic, to find a fusion of life and creativity, a kind of philosophical stone of art ... at that time and among those people, the “gift to write” and “the gift to live” were regarded almost equally ... An artist who creates a “poem” not in his art, but in life, was a legitimate phenomenon at that time”.

So, the Silver Age is a specific, unparalleled time in history, marked by a number of characteristic features reflected in works of literature and art, as well as in the fate of people who became the living embodiment of that era.

This period provides particularly vivid examples of the conscious mythologization of one's own personality, when the poet, no longer satisfied with the role of the demiurge in a purely literary incarnation, forms his personal everyday image in accordance with his own philosophical and aesthetic views. This image should, according to the creator, unite, on the one hand, the so-called lyrical “I”, and on the other hand, become the complete embodiment of the worldview position in a real, human destiny. This kind of effort can be conditionally called life-creating behavior.

It should be noted that the purpose of such auto-mythologization is not to hide and obscure the true content of the personality with “selfish intentions”, but on the contrary – the desire to most adequately express the deepest essential attitudes of this individual. Behavioral activity is aimed at revealing what is “more real than reality itself”, at the destruction of incorrect, “random” features and the exposure of the true creative face. The unity of life and creativity, not only declared, but also consistently carried out in everyday everyday situations, is one of the distinguishing features of the Silver Age period.

There are many examples of this. Let us take, for example, the numerous reminiscences of the worldly eccentricities of Andrei Bely. Bronislava Pogorelova, the sister of Valery Bryusov's wife, cites such an episode, for example: “With an inspired face, the tone of an obsessed and a prophet, he began to talk about how he was visited by the Unicorn, his old friend. And it was by no means a symbolic name for some human being. No, B.N. repeatedly emphasized: REAL Unicorn. Here B.N. returns, according to him, to his room. And in the twilight, against the background of the window, he clearly notices: The Unicorn is already here and friendly nods with its single horn. An interesting conversation begins”.

An interesting reaction to the story of the “Unicorn” Valery Bryusov. According to the memoirs of Bronislava Pogorelova, he explained this fact very simply: “B.N. so used to talking about him. He almost believes himself. And he's so comfortable...”

A similar impression is produced by the episode with Andrei Bely, repeatedly reproduced by various memoirists, “crucifying” himself on the wall in the course of an ordinary conversation. Let us turn to the memoirs of Boris Zaitsev: “His figure was rushing about against the background of the wall, however, like a tomb wreath in the wind. Suddenly he spread his arms in a cross, pressed his back against the wall, turned completely pale, exclaimed: “I am crucified! I'm crucified in life! Here is my way... Everyone rejoices, but I am crucified...”

Such behavior is by no means the exaltation of a narcissistic poet, not the cheap play of an actor who arranges a farce for the amusement of the viewer. Behind such Bely's behavior one can see, on the one hand, absolute self-dissolution in transcendental harmony, and, on the other hand, the often realized impossibility of combining the visible and invisible worlds.

And how can one not recall the story of the relationship between Nina Petrovskaya, Andrei Bely and Valery Bryusov, incredible in terms of intensity of passions? This is the clearest example of the creation of a literary myth on a non-literary basis. According to Vladislav Khodasevich, Nina Petrovskaya's literary gift “was not great. The gift to live is immeasurably greater”. At first glance, the drama of everyday life, performed by people who do not separate their personal destiny from literary creativity and, moreover, from comprehending the philosophical depths of being, has become the embodiment of the tragic worldview not only of its characters, but of the whole era. This story, which gave literature several poems by Bely and Bryusov, as well as the novel The Fiery Angel, was not limited to “literary consequences”. It is no coincidence that many different people, recalling that time, invariably turn to this plot – probably contemporaries saw in it something more than a banal love triangle. As for Nina Petrovskaya herself, these events obviously became the culmination of the “poem of her personality”. According to the same Khodasevich, “Nina's life was a lyrical improvisation, in which, only applying to the same improvisations of other characters, she tried to create something integral – “a poem from her personality””.

Andrei Bely, Nina Petrovskaya, Valery Bryusov

The range of “lyrical improvisations” in the literary environment of the turn of the century was very wide – from Aleksandr Dobrolyubov to Viktor Hoffmann, from Igor Severyanin to Vladimir Mayakovsky. Note that the idea of life-creation was not associated exclusively with the circle of symbolists. If not a poem, then a story from his personality was created by the head and founder of acmeism, Nikolai Gumilyov. From early youth, believing in its exceptional significance for the development and improvement of the human race and in general for the world order, Gumilyov, already in his youthful, rather weak verses, began to create for himself the halo of an extraordinary personality. And not only in poetry. Many of his everyday actions were dictated by the same desire – to create a heroic biography for himself. The circumstances of his death and courageous behavior during the execution in 1921 complete the picture. And although this probably sounds somewhat cruel, but, nevertheless, “made” life and real death gave the world the myth of Gumilyov.

Nikolai Gumilyov. Tsarskoye Selo. 1914

A characteristic feature of the myths generated by the Silver Age was that they embodied not only the subjective impulses of their bearers and creators, but also the objective historical situation. The turn of the century, with its tragic breaks and the extraordinary lightness of being, with its disastrous merriment “at the gloomy abyss on the edge”, with its games over the abyss, was fertile ground for the creation of legends. The era itself, full of a sense of the end, probably dictated the desire to leave behind something more than a book of poetry or a volume of prose. Perhaps many of the people who lived then deeply felt that the blossoming complexity and the endless alternation of the seasons were being replaced by eternal winter. Winter, when beautiful and tragic tales will be so necessary for the few left by the fading fire of Russian culture.

In the future, these legends were confirmed and consolidated in the memoirs of contemporaries. In the course of this process, the “crystallization” of myths was completed, that is, they took on an almost complete form, allowing only minor additions. But it should be noted that the subsequent “literary existence” of such established legends sometimes brought amazing surprises – certain interpreters from among the descendants sometimes filled the established form of myth with a completely new, previously uncharacteristic ideological content.

This phenomenon is especially typical for the period of postmodernism, when any creative personality (as well as its legacy) can be considered as a kind of semantic unit that is able to enter into completely unexpected semantic and associative connections with other similar units. These “blocks” can be arbitrarily arranged in any coordinate system, obtaining, of course, a completely different content. Postmodernism, which considers any phenomenon in the history of culture as the necessary material at hand, has given the world unprecedented examples of more than free handling of historical and literary facts, not to mention literary myths.

The myths of the Silver Age, striking in their diversity, nevertheless have one thing in common. Each name, surrounded by a halo of legends, strikes, first of all, with its originality, its independence, each personality, in the words of Osip Mandelstam, stands “separately with a bare head”.

III.

Among the variety of unique heroes of the Silver Age, there were those who, it would seem, were destined to get lost against this bright background. One of these, at first glance, hardly noticeable people is the Tsarskoye Selo poet Count Vasily Alekseevich Komarovsky. Today, few people remember the existence of such a poet, the general reader is practically not familiar with his work. The figure of Komarovsky flashes among the characters of the second, and even the third plan in a few memoirs. It is characteristic that in Letters from a Diary Anna Akhmatova, recalling the meetings of the Guild of Poets, wrote Komarovsky's name on the side and in pencil. Such a place in the history of literature of the Silver Age was prepared for him by fate.

Various modern sources contradict each other regarding the dates of his birth and death. (The monumental volume published in 2000, edited by I. Bulatovsky, I. Kravtsova and A. Ustinov, did not change the situation much. Ridiculous articles about Komarovsky, based on speculation and rumors, have been published and continue to be published. Even on a solid website dedicated to Anna's work Akhmatova, the author of the article about Komarovsky, Lisa Guller, writes: “On September 21, 1914, Vasily Komarovsky committed suicide” – www.akhmatova.org. As we will see below, both the date and circumstances of the poet's death are distorted here.) And the little information that can be gleaned from contemporaries’ memoirs belongs mainly to the field of literary legends. According to G. Ivanov and S. Makovsky, Count Komarovsky, being a good poet, was first of all a madman who spent a significant part of his life in psychiatric hospitals, and the rest – a recluse in Tsarskoye Selo. Picking up this idea, various memoirists attribute numerous deeds and strange speeches to Komarovsky. Thus, there is a “crystallization” of the legend, gradually acquiring an infinite number of everyday details. Most of the memoirs known to us, to put it mildly, sin with inaccuracies, and sometimes with a deliberate distortion of facts. Of course, fans of cheap effects may like this version – after all, among the writers of those years there were many people who were at least strange. But, as often happens, the legend of the mad recluse threatens to obscure the true face of the outstanding poet.

Let's try, without pretending to be a complete research, to restore as truthfully and accurately as possible the true circumstances of the life and work of Count Vasily Alekseevich Komarovsky. But first it is worth noting one important, it seems, point. Most of the materials presented below were not available to the authors who wrote about Komarovsky. Therefore, the conclusions drawn here are based not only on a thorough study and comparison of already known information, but also on materials discovered as a result of our own research. And although it cannot yet be said that there are no white spots in Komarovsky's biography, in the first approximation it is drawn quite clearly.

The genealogy of the Komarovskys has been documented since 1626. In the Materials for the Genealogy of the Counts and Nobles of Komarovsky (Novgorod), compiled by the poet himself, we read: “The copy of the Belozersky books of letters and measures by Prince Shakhovsky and clerk Nikita Kozlov of 134 and 135 in the Palmesere Volost in the estates was written for a foreigner for Pavel Komarovsky, which ahead of Alexei Balashiv was half the village of Kondratovsky, Artyomovskie, too, and the other half of that village behind Ivan Ageev”.

V.A. Komarovsky took a serious interest in his pedigree throughout his life. The documents cited by him in the already mentioned Materials... documents (in particular, letters from Marina Mnishek and voivode Pleshcheev) suggest that his clan is of even more ancient origin and originates from “Peter from Komarov on Lentov and Orava (Hungarian county against Belgrade)”, which received the Lithuanian county “forever” from the king of the Hungarian Corvinus back in 1469. However, confirmation or refutation of this version requires further research.

For almost two hundred years, the Komarovskys were Novgorod landlords, and little is known about their lives. However, starting with the poet's great-grandfather, Evgraf Fedotovich, the status of the family changes dramatically, and a new countdown begins: in May 1803, Evgraf Fedotovich was elevated to the dignity of a count of the Holy Roman Empire by the Austrian emperor Franz II.

About Count E.F. Komarovsky has now written quite a lot, so we will dwell only on the main points of his biography. Born into the family of an official of the palace office, Evgraf Fedotovich was brought up in the St. Petersburg boarding houses de Villeneuve, Lenk, I.Ya. Masson. He was married to Elizaveta Egorovna Tsurikova (V.N. Toporov erroneously calls her Tsuranova.). In 1786, in his translation from French, the novels Innocence in Danger, or Extraordinary Adventures by Nicolas Restif de la Bretonne and A Vessel of Miscellaneous Creations of the Marquis de Vargemont, containing moralizing stories, stories, anecdotes and other were published. However, already in 1787, literary studies were interrupted by military service, which, however, allows him to move up the career ladder.

His track record looks impressive. And in fact: adjutant of the Izmailovsky regiment, adjutant of the Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich, adjutant general of Emperor Alexander I, commander of a separate corps of the Internal Guard, senator. During the Italian campaign of Suvorov, he participated in the battles of Addi, Nova, Trebia and others. He was the temporary military governor of two parts of St. Petersburg during the flood on November 7, 1824. It was he who, on December 14, 1825, was sent to Moscow for a genuine act of abdication of the Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich, and then, a year later, he participated in the Supreme Criminal Court over the Decembrists. Having lived a long, eventful life, Evgraf Fedotovich left to his descendants valuable memories of the historical events of the time, of which he was a witness and an active participant.

Interested in the history of his family, Count Vasily Alekseevich Komarovsky paid special attention to his grandfather, Yegor Evgrafovich (1803-1875), whose biography he studied in detail. And this, of course, is not accidental.

E.F. Komarovsky: the great-grandfather of the poet, E.E. Komarovsky: the grandfather of the poet, A.E. Komarovsky: the father of the poet

Egor Evgrafovich was brought up in the St. Petersburg Jesuit boarding school. His tutor in childhood was the famous French emigrant Baron, who later founded a private men's school in Moscow. Studies in ancient languages, general history and literature, the assimilation of classic principles determined much in the humanitarian foundations of his personality. “His thinking bore”, an unknown author writes about him, “clear traces of the theological dialectics of the Jesuits. He knew the ancient writers, mostly Latin, to perfection, and he spoke French orally and in writing with that elegance that contributed to the special charm of his witty conversation... It was a scion from emigrants, but with purely Russian, local shades in its worldview and in its national predilections”.

Much says about Yegor Evgrafovich as a person with deep intellectual and creative interests. The nature of these interests can be partly judged by the circle of his acquaintances and friendships. Even during the Turkish campaign of 1828, he met A.S. Khomyakov. Later he becomes a friend of I.V. Kireevsky, who dedicated his open letter On the nature of the enlightenment of Europe and its relation to the enlightenment of Russia to him. Yegor Evgrafovich's response letter was published in the Russian Archive. Dealing with historical, philosophical and religious problems, he begins to write a book, which he thinks to title “Diapasons historiques, par un Slave de la Communion dite orthodoxe – a kind of mystical experience of the philosophy of history”, according to V.A. Komarovsky, but never finished it. He was a man completely immersed “in the highest demands of the spirit”.

But not only this feature attracted V.A. Komarovsky in the figure of a grandfather. Yegor Evgrafovich was married to Sofia Vladimirovna Venevitinova, the sister of the poet D.V. Venevitinov. The Venevitinovs, as Vasily Alekseevich established, were related to A.S. Pushkin. Thus, a thin thread was stretched through the grandfather's family, connecting the two poets with family ties.

Stories about grandfather V.A. Komarovsky heard from his daughter Anna Egorovna. It was she who told him the story of how, a few days before his death, Pushkin met E.E. Komarovsky and asked him to point to some book about the duel. In general, she was a kind of intermediary between her father and nephew. Anna Egorovna was a chambermaid and maid of honor to Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna, widow of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich. She spent half a century of her life at court, witnessed many events. In her living room, she received famous writers – Turgenev, Dostoevsky, Vl. Solovyov and others.

Yegor Evgrafovich had nine children. One of the younger ones, Alexey Yegorovich, is the poet's father. He did not differ in anything outstanding, his official activity also did not characterize him much, but he was flesh from the flesh of that noble environment in which his ancestors and he himself grew up. Lively and friendly, Aleksey Yegorovich behaved freely and simply with people, was sociable and had many friends. Public matters were of little interest to him. His spiritual warehouse is more said by how easily and beautifully he painted, remaining within the limits of amateurism, which sometimes reached a high level. In the few surviving drawings of his – sketches of the sky, clouds over the sea, light and masterful sketches of programs for musical charity evenings, painting fans. As a boy, he made a prayer book with a heading for each prayer as a gift to his younger sister. A box was painted by him: on a white background, a scene in the spirit of the 18th century. In 1882, while living in Lizin, he painted an image of St. Alexander Nevsky for the local church.

IV.

Vasily Alekseevich Komarovsky was born in Moscow on March 21 (April 3), 1881. His father Alexei Yegorovich at that time was a real state councilor, the master of the imperial court, his mother was Alexandra Vasilievna (nee Countess Bezobrazova). The family had three children born with a difference of one year: the eldest – Vasily, the middle – Yuri and the youngest – Vladimir.

The children lived in a friendly family, brought up in the firm Christian rules and traditions of the noble culture. Summers were spent in the estate of Lizino, Tula province, or, more often, in the village of Raksha, Tambov province, with Alexandra Vasilievna's father, Vasily Grigoryevich Bezobrazov. Raksha is a gift from Emperor Paul to General Glazov, who commanded his Gatchina troops. At the beginning of the 19th century, the estate passed to G.M. Bezobrazov, who married the daughter of Glazov. Memories of the time spent here are reflected in many of Vasily Alekseevich's poems, including one of the last, posthumous, published in Apollo. For all three children, this place was unique, the only place where they came at different ages – to breathe their native air and gain strength.

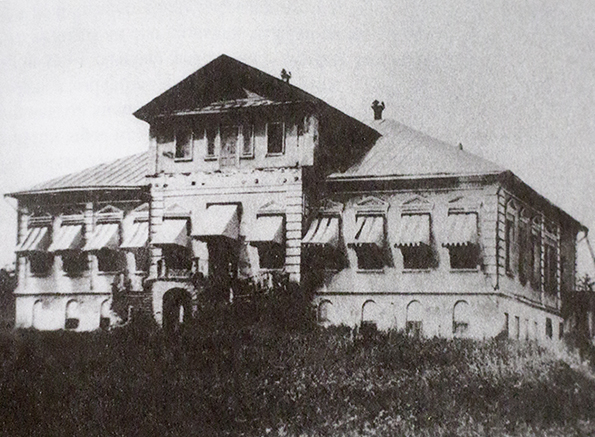

Raksha estate. Watercolors by V.A. Komarovsky, the younger brother of the poet

These were black-earth, semi-steppe places where life seemed to be still full of established customs and peace.

The path stretches through a shaggy meadow,

And the spirit that intoxicates the heart rushes around,

And the clouds swirl in a swollen string

Above the white church and the white hospital.

The fields came close to the garden. In the old house of the Pavlovian time, inhabited by more than one generation, a large family gathered around the grandfather and grandmother of the Bezobrazovs. The children came here together with Lydia Mikhailovna Balkashina, who raised the brothers, and the girl Dunyasha. For the summer, a student tutor was invited, who worked with children and himself joined the young company.

In the mornings, everyone gathered in a large beautiful hall with windows open to the garden. Grandfather and grandmother sat in their places of honor. Greeting, the grandchildren kissed their hand. Children were not allowed to interfere in the conversations of the elders.

Trying to educate in strict rules, the old people at the same time pampered their grandchildren as best they could. For them, a croquet was ordered from Moscow, riding horses were selected. The name day was solemnly celebrated: the day began in the church with mass with a prayer service and ended with illumination and fireworks.

Vasily Komarovsky in childhood, his mother, with his mother and brother, his father, Raksha estate

Classes were held without much interest in them on the part of both students and teachers. The only exception, perhaps, was the elder brother Vasily, who was critical of the tutor's classes. “... Our student completely fell in the opinion of our Vasya, he had not heard about Renan, only you please do not reproach Vasya with this, then he will not express anything,” Lidia Mikhailovna reported in a letter dated July 5, 1899 to Alexei Yegorovich. And then she continued: “I have a war with Vasya almost every evening, they go to bed late and he piles everything up to his bed and lies with a book and reads so proudly. And I prove to him the inappropriateness of such behavior”.

In Raksha there was an old manor library, which was especially fond of the young poet:

It used to be from fuss, boyish din,

I went here – Columbus, Vasco de Gama –

In the new garden and poisons and medicines,

– he later recalled. But that was later.

In the mid-1880s, V.G. Bezobrazov bought a large dacha in Yalta and moved there from Moscow. It was a large three-story house with balconies and a large garden, standing on a high place near the dacha of the Emir of Bukhara (the house has been preserved). Moving V.G. Bezobrazov also attracted his relatives to the Crimea. In 1884 or 1885, Alexei Yegorovich, the poet's father, bought a plot in Yalta and built a two-story cottage on it. Going to paint the living room in it, he took lessons in fresco painting from an Italian artist.

But these plans were not destined to come true. At the age of 27, Alexei Yegorovich's wife becomes mentally ill. The details of the disease are unknown. A.E. Komarovsky places his wife in a private hospital, where she was forced to stay until her death, which followed in 1904. Children were not taken to her, therefore, from the age of five, V.A. Komarovsky grew up without a mother. In addition, he began to have seizures of childhood epilepsy. During exacerbations, they were repeated several times a day. On the recommendation of doctors, he was repeatedly taken abroad for treatment.

The difficulties that fell to the lot of Alexei Yegorovich – caring for a sick wife, children, official and household affairs – were complicated by the fact that he himself was not distinguished by good health. Father-in-law – V.G. Bezobrazov – tried to help him in raising children, gave advice on financial affairs, sent experienced people to check the economy on the estate, where the manager was in charge. His letters to the son-in-law V.G. Bezobrazov signed: “your friend and father”.

In 1898 V.A. Komarovsky, apparently, comes to St. Petersburg for the first time: his father gets the position of the manager of the court of the Prince of Oldenburg. Vasily Alekseevich lives during this visit with his aunt, Lyubov Yegorovna, maid of honor of the Grand Duke's court (Preobrazhenskaya Street – now Radishcheva, 30, apartment No. 8). Lyubov Yegorovna was very kind and sympathetic. Not being a beauty, she was attractive in her own way, which is well conveyed in her portrait by P.I. Neradovsky, located in the Yaroslavl Art Museum. Subsequently, life closely connected L.E. Komarovskaya with her nephew.

Shortly after moving to St. Petersburg, Alexei Yegorovich fell seriously ill and the doctors advised him to go south. For some reason, Egypt was chosen for this purpose, where he goes with his sister Lyubov Yegorovna. Photographs taken during this trip have been preserved: Alexei Yegorovich in a tropical helmet riding a camel, who is held by the reins of Lyubov Yegorovna. Both are tanned, thin, small and sad...

A trip to Egypt did not help. Returning to Russia, Alexey Yegorovich Komarovsky dies. The final diagnosis is stomach cancer. A.E. Komarovsky was buried at the Tikhvin cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. Five years later, his wife was also buried there.

V.

In 1899 V.A. Komarovsky lives in Yalta with his grandfather V.G. Bezobrazov and studies as a semi-external student at the Yalta gymnasium. On August 25, 1899, he enrolled in the Moscow Imperial Lyceum in memory of Tsarevich Nicholas, where he studies for one year, being a visiting pupil. Matriculation No. 862 is issued to him on June 1, 1900.

At this time, V.A. Komarovsky already lives in Raksha. On June 10, 1900, he applied for enrollment as a student at the law faculty of St. Petersburg University. He spends the second half of the summer before exams at his father's estate, Egoryevsky.

On July 27, the petition was accepted and in the fall of 1900 V.A. Komarovsky, together with his brothers, also enrolled in the university, settled in Kosoy Lane (now - Gunsmith Fedorov Street) in house number 13, next to the Summer Garden (the house has been preserved).

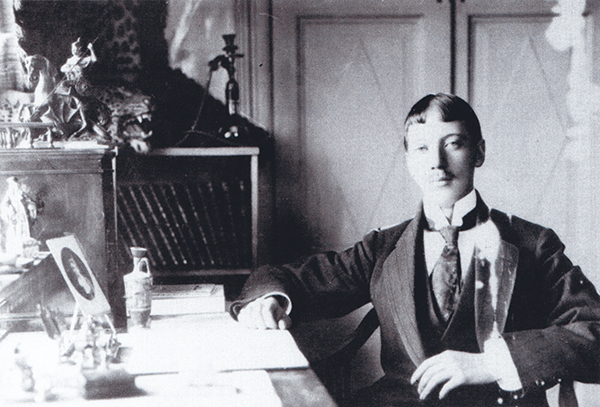

Vladimir, Yuri, Vasily Komarovsky and Sergei Mansurov. Mid 1890s

In the summer of 1901, V.A. Komarovsky travels to Germany. Together with his grandparents Bezobrazovy and family friends Sverbeev, Mansurov and Neklyudov, he visits the Black Forest and Dresden. There Vasily Alekseevich undergoes a course of treatment and gets acquainted with museums. The trip probably had a big impact on him. In any case, on November 3, 1901, Komarovsky filed a petition for his transfer from the Faculty of Law to the Faculty of History and Philology.

He spends his winter holidays in a boarding house somewhere in Finland, makes a trip to Imatra. In the summer of 1902 he lives in Raksha, and in the autumn – in Gunch, the estate of the Kossikovskys, where he becomes close to his cousin Apollinaria Vladimirovna Kossikovsky. Eleven years later, The First Pier will be opened by the only poem of this period known to us, dedicated to A.V. Kossikovskaya.

* * *

Apollinaria Vladimirovna Kossikovskaya

«The garden today is a quiet shiver

And shrouded in mist,

A limp leaf at its foot

Dropped and confused.

He makes noise, makes noise widely,

Oak forest, neighboring forest.

How sad, how deep

This song is the last one in anguish.

My dear friend went to the field,

For the wolves, good luck.

I'm guessing a little...

Well, in the evening I will cry».

The time of resettlement in Tsarskoye Selo, apparently, is 1906. Here Vasily Alekseevich and his aunt Lyubov Yegorovna rented a rather modest apartment on Magazeynaya Street in Palkin's house. (Magazeinaya, 94 according to pre-revolutionary numbering. In 2010, in the year of the 300th anniversary of Tsarskoe Selo, a memorial plaque was installed on house No. 66 on Magazeinaya Street with the inscription “In this building from 1906 to 1911 lived the famous Silver Age poet Count Vasily Alekseevich Komarovsky”. This controversial statement needs to be verified. The house is not too similar to that described by contemporaries and is located, although nearby, but not quite in the right place. In addition, on the website of a real estate agency selling apartments in this house, as the date of construction indicated 1917). The family of Baron E.F. Taube lived in the same house, to whom Komarovsky dedicated one of his best poems The Hunt, beginning with the line “The Prince-Bishop is prancing today...”. The wife of Baron Maria Vladimirovna is dedicated to the verses “Away from people, from light lines...”

HUNTING

Bar. E.F. Taube

The Prince-Bishop is prancing today.

The retinue rides skewbald horses.

In the pines the wind dances furiously,

Fluently curls in thick gray hair.

Everywhere this deep autumn

She lay down to the brown, gray forests;

Where curled up in the northern pines

Smoke, and dark dampness, and haze.

And laughs and full of barking

The air, humid-salty, around.

And in the fog we barely notice

A shining cross on the cathedral.

Proud galloping hunt

Where are the recent harvests of oats.

Prince-Bishop – today's concern

Only these funny dogs!

* * *

Baroness M.V. Taube

Away people, from light lines,

I built a new house for myself.

Built a marble triclinium

And he covered the spring with a stone.

Hills blowing up twice with a plow,

I sowed with a trembling hand.

And they began, behind a magic circle,

Ears, silence, peace.

And the garden is noisy. The waters sway

Accepting the autumn star.

But today I, in the house of freedom,

I'm superstitiously waiting for someone.

Will he confuse with an immodest echo

Sheets of fading alleys;

And slander with noisy laughter

Prayer fields.

Vasily Komarovsky and Lyubov Egorovna Komarovskaya in Tsarskoye Selo. 1900

The circle of acquaintances of the poet and his aunt Lyubov Yegorovna was quite narrow, friends were not numerous. But with the Kardovsky family – the artist Dmitry Nikolaevich, the artist Olga Ludvigovna Della-Vos-Kardovskaya, their daughter Katya – they became friends. The Kardovskys moved from St. Petersburg to Tsarskoye Selo in the autumn of 1907. Their acquaintance with Komarovsky dates back to the spring of 1908. Vasily Alekseevich visited the Kardovsky house often, because he lived close enough. Making his usual walks along Tsarskoye, he sometimes stopped by them without warning. From various reminiscences, it is known that in the Kardovskys' apartment he read aloud his poetic and prose works. In the autumn of 1908, Komarovsky met here N. Gumilyov, who lived on the floor above, and a little later – with A. Akhmatova.

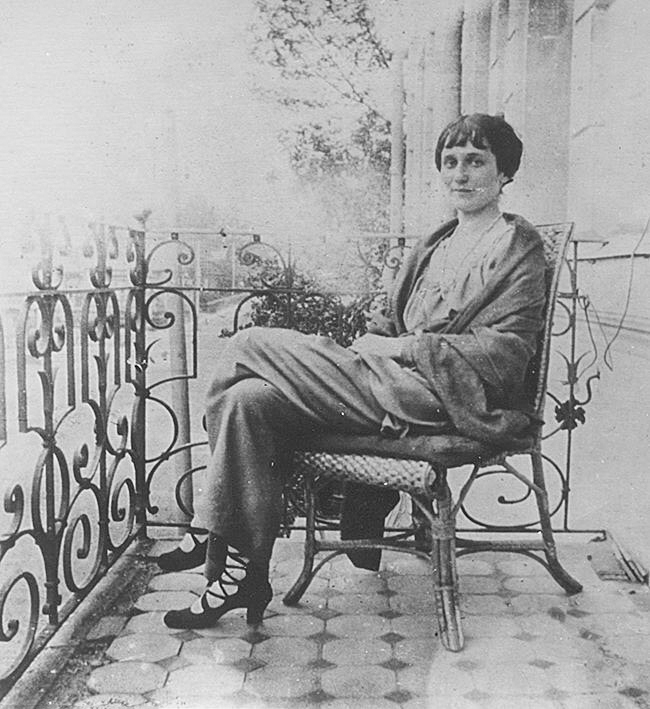

Anna Akhmatova on the balcony of the artists Dmitry Kardovsky and Olga Della-Vos-Kardovskaya. Tsarskoye Selo. 1915

Nikolai Punin in his diary gives a story about Komarovsky's acquaintance with Akhmatova: “Count Komarovsky met Gumilev somewhere and paid him a visit in the house on Bulvarnaya Street (where Gumilev, who had recently married, lived then). An. was not at home. When she arrived, Komarovsky stood up, bowed broadly and, approaching with his heavy gait, stooping to An.'s hand, said: “Now the fate of Russian poetry is in your hands”. ... An. she remembers this meeting and told me that she was very embarrassed...” Komarovsky at that time did not yet know that Akhmatova wrote poetry, he just wanted to be extremely polite. Subsequently, friendly relations were established between them, resulting in an exchange of poetic messages.

ANSWER

V.A. Komarovsky

What strange words

Brought me a quiet April day.

You knew I was still alive

Passionate scary week.

I didn't hear those calls

That floated in the glaze clean.

For seven days that copper laughter sounded,

That cry flowed silvery.

And I, covering my face,

As before eternal separation,

Lying and waiting for her

Not yet called flour.

Many of Komarovsky's poems may have been inspired by his friendship with Akhmatova.

* * *

Burning red flowers of summer

The wine in the glass shone brittle;

From the flaming goblet

I drank – while you sang.

But in autumn the horn blows and is silent.

There is a high fence around the gardens;

How many of them, wandering along the roads,

And none of them need

Haughty bitterness of your evening braids.

Where frost crunches underfoot at night

And the smoky crops will chill.

Where muddy jets are night rehashes

About the freezing sadness

My love – you know by heart.

However, some of their contemporaries believed that there was not only friendship. So, in the already cited diary, N. Punin writes about Komarovsky: “In one of the attacks of insanity, he told An. that she was a Russian icon, and he wanted to marry her. Aunt Komarovsky (the so-called aunt Lyuba) was afraid of Vasily Alekseevich's acquaintance with An., thinking that he would fall in love with her; she was afraid of “an affair with a bohemian””.

The acquaintance of Komarovsky with N. Punin dates back to 1910. Punin at that time was a student at St. Petersburg University, where he studied art history, especially interested in the Renaissance and Byzantium. Komarovsky, on the other hand, was compiling the Table of the main painters of Europe from 1200 to 1800 – the first work of this kind in Russia, which made it possible to trace the mutual influence of various schools and trends in the visual arts. Common historical and art history interests undoubtedly contributed to the rapprochement and friendship between Punin and Komarovsky. In unpublished memoirs, Punin described his meetings with Komarovsky and his conversations with him as follows: “It was possible to climb up the creaky wooden stairs to his bedroom. Downstairs was a small office. The footman Dmitry in a gray jacket opened the front door, the fox Jack barked; and if Komarovsky was not in the office, then Dmitry went upstairs and after a while I heard Vasily Alekseevich going down the stairs heavily and noisily and, before he even entered the door, he loudly said in his guttural and somewhat hoarse voice: “Hello, Nikolai Nikolaevich. He was a tall, broad-shouldered, stooping man with a close-cropped head; shaven apoplectic face; brown, kind, lively, strange looking eyes... Our friendly conversations in his office (sometimes we walked around the Catherine Park, skirting the lake), like all my friendly conversations with men, usually did not go beyond art... but I soon realized the superiority of his culture, its extraordinary density, and this undoubtedly contributed to the fact that he felt like my mentor”.

Nikolai Punin

Komarovsky was not only a mentor for Punin. Through the mediation of Vasily Alekseevich, Punin published an article in Apollo devoted to Byzantine art, which became his journal debut. On another occasion, Komarovsky recommended him to P.I. Neradovsky, who was then in charge of the art department of the Russian Museum of Emperor Alexander III. On this recommendation, Punin was invited to work there and continued to collaborate with the Russian Museum until the early 1930s. Thus, Komarovsky not only had a great influence on Punin's spiritual development, but also contributed to the practical realization of his personality.

VI.

In July 1911, an important meeting for the creative fate of Komarovsky took place – an acquaintance with Sergei Makovsky, editor of the St. Petersburg magazine Apollo. In his memoirs On the Parnassus of the Silver Age, Makovsky writes that he moved to Tsarskoye Selo immediately after his marriage, in 1910, but does not say where he met Komarovsky and how their relationship developed. Nevertheless, it was precisely this acquaintance that brought Vasily Alekseevich closer to the editors of the Apollo magazine and the Guild of Poets. Komarovsky attends the St. Petersburg editorial meetings of the Apollo and Tsarskoye Selo meetings of the Workshop. In 1912, his first publication appeared in Apollo – five poems and the beginning of the story Sabinula. A little later, reviews of his The First Pier and Table of the main painters of Europe will be placed here, then an obituary on the death of Komarovsky, and in 1916 – a posthumous selection of his poems. For many years, Apollo will become practically the only available source of information about both the poet's creative heritage and about himself. This fact was caused by the extremely small circulation of The First Pier (it is still not known exactly, presumably 450 copies), most people who personally knew Komarovsky well and wrote about him later did not have this book (for example, Sergey Makovsky). Even the niece of Vasily Alekseevich Komarovsky, this collection appeared only after 1985. Therefore, almost everyone who wrote about Komarovsky referred to Apollo.

Sergey Makovsky

1911-1912 years – the most active and fruitful time in the life of Komarovsky. At this time, almost most of his well-known poems were written, in addition to the already mentioned story Sabinula, work began on the novel Before Tsushima. Very little is known about this novel, apparently completed, but, unfortunately, lost, Vasily Alekseevich himself did not read it to anyone. N. Punin, who knew about the existence of the novel, once asked Komarovsky to read at least a paragraph from it, but to no avail: “I can’t,” he said, “I don’t want to quarrel with the dynasty”. In 1915, after the poet's death, D. Svyatopolk-Mirsky (Komarovsky's executor) read the novel in the Kardovskys' house. Anna Akhmatova was present at this reading: “The other day R. Yakobson and his wife visited me. Again about Komarovsky (?!) What did he give them? – We talked about Komarovsky's novel Before Tsushima. I only remember how the sister of the hero, a St. Petersburg society lady, having learned that her brother is dying, utters an immortal phrase: “Today I need to go to bed earlier – Je dois être fraiche pour la панихида...” (I must look good at the memorial service – N.M.) I listened [how] when D. Svyatopolk-Mirsky (Komarovsky's executor) was reading the novel Before Tsushima at the Kardovskys' in 1915 (in Tsarskoye). When in 1937 I asked Mirsky where the manuscript was, he assured me that it was gone. That seems to be all I know about the case”.

Dmitry Svyatopolk-Mirsky

In addition to creative activity, the period of 1911–12 was marked by a significant expansion of Komarovsky's circle of acquaintances. He starts a correspondence with A.D. Skaldin, a poet, an acquaintance of Blok. He meets the leading ballerina of the Mariinsky Theater T.P. Karsavina, with orientalist V.V. Golubev, the author of articles on the culture of the East and a well-known collector. Persian and Turkish miniatures from the Golubev collection were exhibited in 1910 in Munich at an exhibition of Muslim art.

The same period also includes the rapprochement of Count Komarovsky with the circle of artists who were members of the so-called New Society, which had as its main goal the organization of exhibitions, than helped young artists at the beginning of their creative path. To all permanent members of this association – D.N. Kardovsky, O.D. Della-Vos-Cardovskaya, I.A. Charlemagne, N.F. Petrov – had common features. First of all, this is the high professionalism of their work, always somewhat gravitating towards graphic in the manner of execution, and, in addition, a commitment to retrospective themes, focused mainly on the estate life of the landowner in the 40s of the 19th century.

Friendship with the Kardovsky family has already been mentioned above. And the rapprochement between Komarovsky and Nikolai Filippovich Petrov led to their joint trip to the Raksha estate, where Petrov painted a series of watercolors depicting the interiors and appearance of the manor house, with which Vasily Alekseevich was so much associated. With another artist who was a member of the New Society – Pyotr Ivanovich Neradovsky – Komarovsky in the fall of 1912 makes a trip to Dresden.

In the Olsufievs' house on the Fontanka, Petersburg. Sitting (from left to right) Yu.A. Olsufiev, L.V. Glebov and A.V. Olsufiev. Standing (from left to right) P.I. Neradovsky, Vladimir and Vasily Komarovsky, S.V. Olsufiev. 1904

The New Society also included the brother of Vasily Alekseevich – Vladimir Alekseevich Komarovsky. The coincidence of their initials led to an unfortunate mistake of modern researchers who claimed that Vasily Alekseevich was also engaged in painting. This is not true. Sergei Makovsky's article Exhibition of the New Society, published in the journal Apollo, refers to the work of the poet's younger brother. There is also placed a reproduction of the sketch of the church painting Heads of the Apostles, which belonged to his brush. It should be noted that Vasily Alekseevich helped his brother in the work on the project of the iconostasis of the church of St. Sergius of Radonezh on Kulikovo field, but this help was not the help of the artist. It is with the work of his brother on the Kulikovo iconostasis that the list of literature on ancient Russian art compiled by Vasily Alekseevich is probably connected. It was written by Komarovsky, includes the works of Buslaev, Filimonov, Likhachev, Sakharov, Rovinsky, Pokrovsky, Trutovsky and other authors, and undoubtedly testifies to the poet's serious knowledge of art criticism on this issue. Yu.A. Olsufiev, but also not as an artist. His professional interests lay in the field of protection, restoration and study of monuments of ancient Russian art. The artistic embodiment of the project belongs to Vladimir Alekseevich Komarovsky and Dmitry Semenovich Stelletsky, a close friend of the Komarovskys and a frequenter of Raksha.

In the Russian Museum, all the works signed by Komarovsky with the initials V.A. undoubtedly belong to Vladimir Alekseevich Komarovsky, the poet's brother (attribution of the State Russian Museum, 1995). The only work that is in the painting department of the State Russian Museum and signed with only one last name, belongs to the brush of the poet's father Alexei Yegorovich and is his self-portrait. Thus, Vasily Alekseevich never had anything to do with professional painting. However, the poet nevertheless painted a little. In 1909, his brother-artist (to avoid confusion, let's make a reservation – Vladimir) presented him with a large sketchbook, in which Vasily Alekseevich drew until the end of his life. This album, containing about 60 drawings of the poet, was kept by the heirs of Yu.A. Olsufiev, then in the archive of the poet's niece A.V. Komarovskaya, who died in 2002. It is enough to compare the professional works of Komarovsky Jr. and these pencil sketches, which is called “for oneself”, in order to assert with confidence that reproductions of his brother were published in Apollo, and Vasily Alekseevich was not and could not be an artist.

VII.

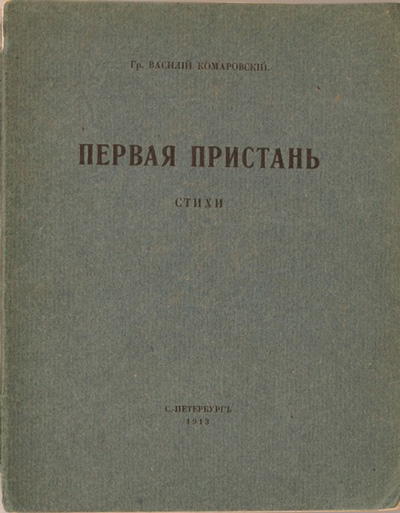

In 1913, the first and only collection of Komarovsky's poems, The First Pier, published by the poet himself, was published. The book was not noticed by critics. Only three reviews are known – in Permskiye Vedomosti signed by El-sky (probably S.V. von Stein), a short review in the in The Day newspaper signed by N.A. (N. Asheshov?), and a review by Nikolai Gumilyov (Apollo, 1914, No. 1–2).

The First Pier. SPb., 1913

In the same year, Vasily Alekseevich and his aunt moved to St. Petersburg in connection with the move there of the family of Baron Taube, with whom they lived in the same house in Tsarskoye. In St. Petersburg, Taube and Komarovsky also settled together, renting a large two-story house at the address: Kamenny Ostrov, 1st Birch Alley, 6. V.A. Komarovsky was not happy with the change of residence. In correspondence with O.L. Della-Vos-Kardovskaya, he repeatedly mentions that any trip to Tsarskoye Selo is a holiday for him, and once he even quotes the following lines from Delvig:

I don't like housewarming,

Here everything withered, there it bloomed.

One is my joy –

See Tsarskoye Selo!

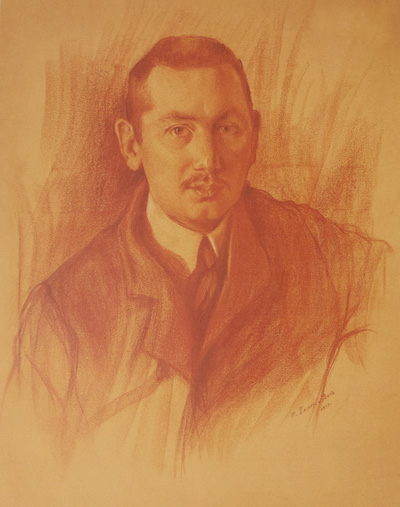

By the way, the last lifetime portrait of V.A. Komarovsky made by O.L. Della-Vos-Kardovskaya on one of these visits to Tsarskoe. Date on the portrait: 1913.

In the summer of 1914, waiting for the proofreading of the Table of the main painters of Europe, which came out after his death, V.A. Komarovsky spends in St. Petersburg, occasionally coming to Tsarskoe Selo. There, visiting the Kardovskys, he meets the artist K.A. Somov. Komarovsky is working on a preface to a book of poems and letters by Sofia Novosiltseva, and is preparing his new book.

Vasily Komarovsky. Portrait by O.L. Della-Vos-Cardovskaya. 1911

His classes, judging by the correspondence, give him a lot of pleasure – whether it’s visiting the tennis championship (“While the poet is not required...” / “Пока не требует поэта...”) or a walk along Tsarskoye (“Life again has brought me...” / “Вновь я посетил...”). Everything pleases him: the smell of cut grass, the beauty of “views”, the air, and even “a beautiful new pavement”... And the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in his opinion, “despite the tragedy, apparently, will defuse military tension”. But it happened differently. Death in Sarajevo triggered World War I.

A week after Germany declared war on Russia, in a letter to Elizaveta Aleksandrovna Bezobrazova, Komarovsky writes about the great events that Petersburg went through: “The people, who only six days ago smashed the tram tracks, mobilized all their forces with seriousness, pride and religiosity... On the day of the declaration of war, I was at a demonstration on the square near the Winter Palace – everyone knelt down, then sang to the Empress, who came out onto the balcony, “Reign at the fear of enemies””. The events of the first days of the war, still distant, but already a terrible reality, undoubtedly greatly influenced the state of mind of the poet. He, like many at that time, feels that he lives “on the eve of the terrible judgment of the human race, and each appears with his own vices and merits”. But the letter, nevertheless, ends on a calm note: “Wait and see”.

Neither live nor see Komarovsky had a chance. We find the most reliable description of the last days of the poet's life in a letter from the father-in-law of Vladimir Alekseevich Komarovsky – F.D. Samarin – to his sister Anna Dmitrievna on September 9, 1914: “I seem to have written that Vasya Komarovsky was in a very nervous state while still in St. Petersburg, which is why Volodya decided to take him away from there. In Izmalkovo, he seemed to be completely calm. But in the last few days he had insomnia and great nervous excitement. Then Volodya decided to take him back to St. Petersburg, but already in Moscow his condition worsened so much that he had to be placed with Lakhtin. Here he was violent for a long time, but towards the end of last week he began to calm down and on Saturday they said by phone that his consciousness was beginning to clear up. However, shortly after this, quite unexpectedly, a heart attack occurred, which is said to often occur with epilepsy. In spite of all measures, the activity of the heart became worse and worse, and finally, on Sunday evening, they made it known that the situation was extremely dangerous. ... He died quite quietly, just faded away. An hour and a half before that, Dobronravov communed him and says that he still quite clearly answered the question of whether he wants to partake”.

Count V.A. Komarovsky was buried at the old Donskoy cemetery in Moscow, near the monastery wall. According to Yu.A. Olsufiev, “It was a gloomy autumn day, but when the coffin was lowered into the grave, then suddenly a bright ray of the sun illuminated it for a moment, as if giving its last tribute to the deceased”.

VIII.

People who knew him closely, who were friends with him and loved him, and sometimes admired his work, also tried to pay their last tribute to Komarovsky. But according to some strange regularity, the image of the poet and the person, rising from the pages of their articles and memoirs, apparently, more and more moved away from the real poet and person, moving into the realm of literary legends.

It is curious that Nikolai Gumilyov, during the life of Komarovsky, laid the foundation for this process in his review of The First Pier. Against the background of the general silence of criticism, Gumilyov's assessment of Komarovsky's creativity (so far only creativity) looked unexpectedly enthusiastic. He wrote about the depth and significance of thought and form, noted the mastery and creative independence of Komarovsky's poems. But at the same time, Gumilyov claimed that these were the poems of a master, but not a teacher. And Count Komarovsky “in all likelihood will never be a teacher, the very nature of his work, lonely and stingy, will prevent him from doing this”.

Nikolai Gumilyov. Tsarskoye Selo. 1907

Gumilev himself, as you know, the position of a teacher in poetry seemed extremely significant and honorable. So significant that for himself he sought this title very consistently. According to the memoirs of A. Akhmatova, Gumilyov even claimed that it was he who “taught Vasya to write, his poems were so four-legged at first”. However, many contemporaries express the exact opposite idea, speaking about the obvious influence of Komarovsky on the young Gumilyov, and not vice versa.

Separately noting those features of Vasily Komarovsky's poetry that were close to Gumilyov as a theorist of acmeism, he, nevertheless, clearly did not dare to enroll the poet in his camp, despite the fact that Komarovsky attended meetings of the Guild. Moreover, he himself asked Komarovsky the question: “But to whose school do you belong, to mine or Bunin’s?”. In all likelihood, Gumilyov never decided this question for himself, and if he did, it was only towards the end of his own life. But a long article about Komarovsky, which he, according to G. Adamovich, was going to write, remained unwritten. Gumilyov never determined the place of Komarovsky in the history of Russian poetry.

“Gumilyov spoke about Annensky and said that he had changed his mind about him. This poet is allegedly “bloated” and insignificant, and most importantly – “neurasthenic”. The only truly great poet among the Symbolists is Komarovsky. Now, finally, he understood this and wants to write a long article about K. ... I remember well how he spoke of him with admiration, put him above all his contemporaries, emphasizing the courageous, worthy character of his poetry. Gumilyov happened to change his judgments. It is quite possible that if he had lived longer, he would have returned to Annensky. But in the last days of his life, he rejected him and opposed him precisely to Komarovsky”. – Adamovich G.V. Letter to W. Tjalsma.

Georgy Adamovich

The “lonely” poetry of Komarovsky, indeed, did not fit into any of the literary movements. There was something indefinable, elusive, but clearly felt in it – what Nikolai Punin later called “originality”. This word was first heard in an obituary published in the Apollo magazine immediately after the death of Vasily Alekseevich. Like Gumilyov, N. Punin highly appreciated the poetic work of Komarovsky, but emphasized: “In order to fall in love with these poems, you need to read them, listen to them, study them, repeating from time to time ... it’s true, you can’t cry over them, but it’s impossible not to be surprised”. Punin is most surprised by the fact that behind the variety of content and the usual rhythmic form, lies “so much bewildered grandeur and madness”. In Komarovsky's poetry, he finds “a dark spirit, poisoned, broken, but heroic, falling, but rebellious, tender, dreamy and capricious, but not at all feminine”, present “somewhere inside”, which “at the first reading... you notice, you only feel, ... in the end, you find it everywhere, you recognize it in every word, in any turnover. And just like Gumilyov, Punin writes that Komarovsky's collection “remained like a lonely flower, warmed only by the young breath of the Muse”.

Nikolai Punin. 1918

But Punin writes not only about the work of V.A. Komarovsky. Emphasizing and deepening the same ideas, he tries to penetrate into the depths of his human individuality, contact with which caused a feeling of anxiety, confusion and fear among those who knew Komarovsky – “the thought of the immortal night, the planets, the depths of the earth, where thick nourishing juices overflow, the dark in the depths of his soul, from where his art grew, unexpected, disheveled, full of some kind of persistent will and confused grandeur. According to Punin, even for those close to him, Komarovsky always remained unexpected and always a stranger. And his death forever deprived them of the opportunity to reveal the secret of the poet and man. Punin writes that Count V.A. Komarovsky was born “to say two or three words, to make a gesture, and left, taking with him the secret of his spirit and his thought... Now we will probably never reveal this secret; only fragmentary and strange memories remained to our share, to which death imparted a bitter poignancy...”.

Thus, the compositional dominant of the legend of Komarovsky was outlined. Its further construction followed the path of overgrowth with details, details, mostly of everyday life, and, not surprisingly, simplification. That incomprehensible, inexpressible and indefinable, which disturbed at first, required a more or less logical explanation. And it was easily found.

IX.

The first step towards certainty, completeness of the image of Komarovsky was made by D. Svyatopolk-Mirsky in 1924. The amazing originality of Komarovsky the poet, which does not allow him to be unconditionally attributed to any literary movement, served as a reason to declare his work “a strange curl to the side, leading nowhere”, a kind of play of nature, confirming the excess of the forces of “creative evolution”. As for his human eccentricity, things were even simpler with her – hereditary madness explained literally everything. And now the “pure game” of Komarovsky's poetry and prose is already being played over the abyss of madness.

Svyatopolk-Mirsky does not at all seek to denigrate Komarovsky. His essay about him is dictated by the desire to remind contemporaries of the existence of an extraordinary poet and person, and perhaps the desire to interest the public in an original figure. But at the same time, all the true originality of Komarovsky disappears, dissolving in the socio-psychological (or rather, psychiatric) constructions of the author, his position, sinning with vulgar popularization.

The position of Svyatopolk-Mirsky, of course, caused objections – and first of all from Sergei Makovsky. He does not share either the literary or social views of Mirsky and, analyzing his article in detail, argues with literally every position of the author. Mirsky for him is not just a critic and memoirist, but a Smenovekhite, a returnee, i.e. clear adversary.

Without dwelling on this controversy (occupying, by the way, one third of the article about Komarovsky), it is worth saying a few words about the position of Sergei Makovsky himself. He defines Komarovsky's place in the history of Russian literature with the term “neoclassical symbolist”. Many and enthusiastically quoting The First Pier, Makovsky draws attention to the stylistic refinement of the poems, the perfection of their poetic form, the paradox and unexpectedness of metaphors and alliterations. It is surprising, however, that as a new, recently reported to him by R.B. Gulem, poems from the category of “improvised lines”, he gives a variant of a quatrain from a work published in the same The First Pier.

Sergei Makovsky did not bypass his attention to the topic of Komarovsky's madness, citing his own version of his death. According to Makovsky, he personally took him to a hospital in Tsarskoye Selo, where Komarovsky died a few days later “in a violent fit (tearing into small pieces everything that came under his arm)”. Above, the circumstances of the last days of the poet's life were described in detail, which have documentary evidence, so it does not seem necessary to dispute such “facts” here.

Perhaps the highest point in the development of the legend of Komarovsky was dedicated to him, an excerpt from the Petersburg Winters by Georgy Ivanov. Let's make a reservation that this book cannot be considered as a memoir, it belongs to a different genre. But in this case, we are not talking about the reliability of the information presented, but about the image that G. Ivanov draws. The simplifications of Svyatopolk-Mirsky are being replaced by an almost parodic reduction of the previously emphasized features of individual originality both in poetry and Komarovsky's personality: “His poetry is brilliant and cold. These must be the most brilliant and most “icy” Russian poems. “Parnassus” Bryusov – in front of him is baby talk. But, as in the voice and smile of Komarovsky, there is something wooden in this brilliance. And something unpleasantly stupefying, as in this room, too heated, too lit, too crowded with flowers. ...How pleasant it is to take a deep breath after the fragrant stuffiness of this house. Stuffiness and something else blowing there – among the Smyrna carpets and Sevres vases...”.

So, the path has been completed. From a tragic mystery to Smyrna carpets and Sevres vases.

* * *

All those who wrote about Komarovsky often used the motives of his work and the circumstances of his life and death to solve other authorial tasks that were not related to Komarovsky proper. So, for example, for Gumilyov it was important to establish the principles of a new literary movement, so he emphasized the acmeist features of Komarovsky's poetry. Mirsky's tasks included, in particular, the promotion of his own views on the history of the development of Russian literature, so he used the personality of Komarovsky as an illustration confirming the reliability of the scale of spiritual values he developed. Makovsky, in turn, arguing with everyone who wrote about Komarovsky before him, seeks, as it were, to clear around the figure of Komarovsky a field sufficient for erecting a slender building of neoclassicism, with which he associates the future of Russian literature as a whole, and at the same time acts as an ideological fighter against Bolshevik theories.

The creative individuality of any creator, be it a poet, writer or artist, inevitably gives rise to myths and legends about his hero. Consciously or unintentionally, they are inevitably woven into the fabric of his biography, giving rise to a different reality, sometimes seeming more real than life itself. As time passes, it can be difficult to separate fiction from truth, but close examination of the subject reveals the truth.

Modern works about Komarovsky, for the most part, unfortunately, are based on the already established myth of the crazy reclusive poet and suffer from numerous factual inaccuracies. The most striking example of this is the notes to the two-volume book by Anna Akhmatova, published in Moscow in 1990, compiled by M. Kralin. Here you can read that “Komarovsky committed suicide shortly after the outbreak of the First World War”. Moreover, a number of fundamental provisions are based on this statement in the interpretation of the imagery of Akhmatova's Poem Without a Hero.

Works continue to be published based on unverified or erroneous information. Apparently, the inertia and unprofessionalism of modern researchers of V.A. Komarovsky. The earlier example of the site www.akhmatova.org is just a special case, there are many such examples. Even on the RGALI (Russian State Archive of Literature and Art) website it is said that V.A. Komarovsky “from 1897 lived in Tsarskoye Selo in the house of his aunt Lyubov Yegorovna”, while now it is documented that the time of moving to Tsarskoye dates back to the end of 1906.

And a completely anecdotal example is a quote from the “famous” Short Akhmatov Encyclopedia by S.D. Umnikov: “V.A. Komerovsky – poet, count, schizophrenic, hanged himself in 1914”.

The personality and creativity of Komarovsky are not limited to his legend. His poetry and prose are waiting for their researcher, as well as many blank spots of his biography. The role of Komarovsky in the history of Russian literature is much more significant than it seems at first glance.